The Big Interview: Brazilian director and screenwriter Dennison Ramalho

Renowned for his horror films, Dennison Ramalho—a protégé of the father of the genre in Brazil—talks to Nick Story in a special Halloween interview about a new era of Brazilian horror films over the past decade (interview first published 28 October 2021)

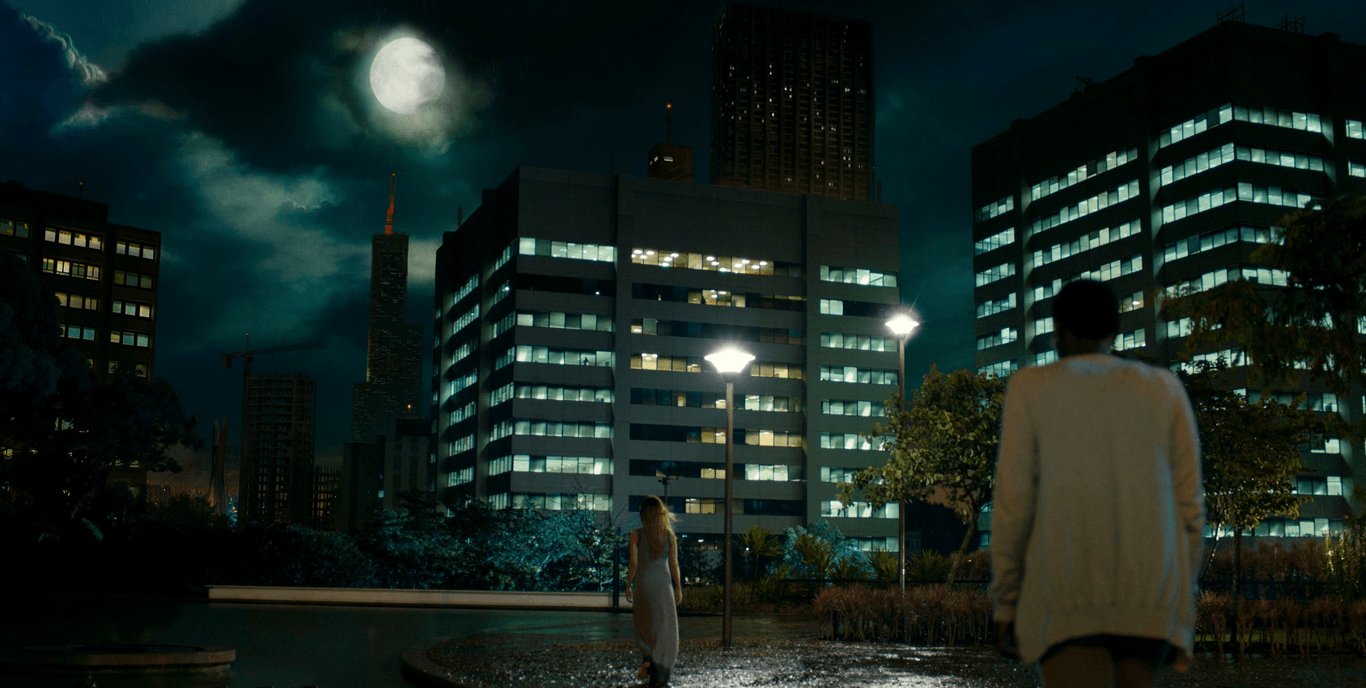

'As boas maneiras' shot in Alphaville

Tell us about how you began making horror films

I am a film and television director and screenwriter who has specialized in the horror genre over the course of my career. I’ve liked this genre a lot, since my childhood. I’ve always consumed a lot of this horror genre. In my early adulthood I spent a lot of time studying it, collecting genre films, reading books on horror cinema, trading references and films with friends who worshipped and studied horror cinema.

I made a decision to follow a career in cinema—and it was a natural decision considering how much of a movie buff I already was. I started with a short film.

I directed four horror short films: three Brazilian productions and an American production filmed in Brazil, which was part of an anthology called The ABC’s of Death 2. I directed one of the episodes that made up the film.

Were your early films a success?

My short films were discovered by international festivals, ones not only specialized in fantasy films but also general film festivals. They were shown in Clermont-Ferrand, at the London BFI Film Festival, at the Fantasia Film Festival in Canada, at the Sitges festival in Spain… So over almost 20 years of making short films, I ended up becoming establised. At the time I started making short films, there weren’t as many people making them as today, so my films were quite prominent. When they appeared at a festival, they won awards in Brazil and abroad.

Are there any other directors in the horror genre that inspired you?

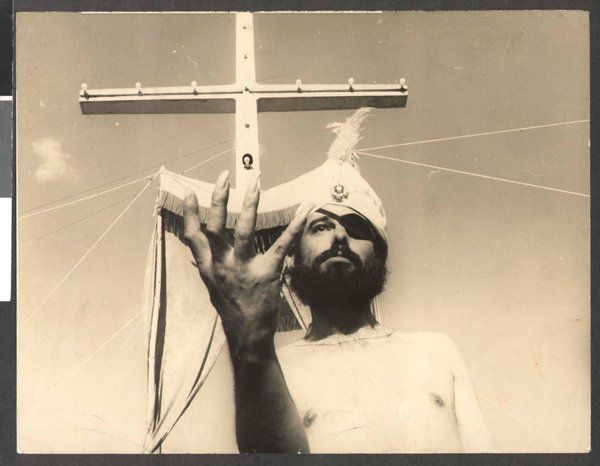

I have a great master, someone who has somewhat of a reputation in horror cinema—a Brazilian director who did the majority of his work between the '60s and '80s—José Mojica Marins. He created a character called Zé do Caixão, known outside Brazil as Coffin Joe.

Director and screenwriter Dennison Ramalho

Tell us about Coffin Joe

Coffin Joe is a character by José Mojica Marins, who was both the director and actor playing the character. He’s unique in the world history of horror cinema because he is the creature and creator who blended together almost seamlessly. His films were discovered outside Brazil in the '90s and became immediate cults.

At Midnight I'll Take Your Soul, This Night I'll Possess Your Corpse, Awakening of the Beast, Hallucinations of a Deranged Mind, The Strange World of Coffin Joe. After these films were discovered by the world, Mojica became an iconic director in the genre, because the cinema he created in the '60s was extremely provocative, extremely violent, iconoclastic, with a lot of eroticism…

He made very extreme cinema for his time, during the military dictatorship in Brazil.

Did you ever work with Mojica?

In the '60s, he started a trilogy of Coffin Joe movies, with his first horror film called

At Midnight I'll Take Your Soul and continued three years later with a second movie, called

This Night I'll Possess Your Corpse. There was a third movie to close the trilogy of this character, called

Embodiment of Evil, which was not made until 2006. I co-wrote the script with Mojica and I was the assistant director of the movie. I dedicated years of my life to this project and it wasn’t my movie, it was my master’s movie.

Before Mojica, were there any other great Brazilian directors in the horror genre?

I cannot speak to what happened in horror cinema in Brazil before 1963 when Coffin Joe’s first film came out. I know there are historians and experts who have written work on the subject and who have found a few titles; a small, timid production that flirted with horror.

Even after Mojica and his commercial success, horror cinema never managed to establish a following in Brazil, or a regular frequency of production. In the '70s and '80s, during the Boca do Lixo ("foul mouth") era, there were some horror films made here in Brazil.

But all or almost all of them were aimed at a male audience. And all or almost all of them were practically horror sexploitation films. They were all horror movies with very sexual approaches, some dipped into softcore porn, made by directors such as Fauzi Mansur, John Doo, and Francisco Cavalcanti. Mojica himself is part of this Boca do Lixo era, since he made horror films in the '70s, films with and without Coffin Joe.

A director from Rio de Janeiro also made some films during the '70s and '80s that the critics did not designate as horror but as “terrir”, which were very chaotic horror comedies. This director was called Ivan Cardoso.

Boca do Lixo explained

The garbage mouth era was a very prolific cycle in Brazilian cinematographic production between the end of the 1960s and the early 1990s. Why is it called Boca do Lixo? There is a region in the centre of São Paulo that housed many film production companies and distributors during this period, and there was a lot of cinema in that region. The entire cinema industry and cycle of “pornochanchada”, Brazilian erotic comedies, was produced almost entirely there. Brazilian x-rated cinema started there as well. The Boca do Lixo cinema has this nickname because their productions targeted the adult audience and were very sexualized.

What is the reputation of Brazilian cinema nowadays?

Up until now, “Brazilian cinema”, in quotes, suffers a little because of this reputation. Even today there are people, older consumers, who don’t watch Brazilian movies because they say that Brazilian cinema is just naked women and swear words, which is a huge misconception. But this infamy of Brazilian films, of erotic cinema and such, was estalished during this Boca do Lixo period, during which some horror films were also made.

This Brazilian cinema period ended with the extinction of Embrafilme, the predecessor of ANCINE—the ANCINE that existed before ANCINE. The Fernando Collor government extinguished Embrafilme, and with the end of Embrafilme Brazilian cinema went through a period very much like what we are going through now: a dry period, with very little production, because public funding for cinematographic production ended.

Were any films made after the Boca do Lixo period?

There was little Brazilian cinema and no Brazilian horror, as far as I know. Until 1998, when I made my first short film, and around 1995 when Peter Bayersdorf, an independent filmmaker from Santa Catarina, started making direct-to-video productions—and he continues till today. He’s a filmmaker, but his production method is not focused on huge commercial exploitation.

Then, in the mid-90s, Brazilian cinema made a comeback. I think I’m part of that comeback, especially of Brazilian horror cinema, with my short films. It’s important to highlight what happened in the wake of Coffin Joe’s film

Embodiment of Evil by José Mojica (released in 2008)—it opened doors for new filmmakers to emerge, such as Marco Dutra, Juliana Rojas, Rodrigo Aragão, Marcos deBrito… They were able to create new feature films, a new production of contemporary Brazilian horror cinema, and because of this I too, a little late, signed up for this new wave with my first feature film, called

The Nightshifter, released in 2019.

Was Moijica part of a wider marginal film scene in Brazil?

Mojica is not part of the marginal film scene because his was fantasy cinema: horror cinema without any kind of political connection. Mojica is an exploitation filmmaker. He really wanted to impress, to shock, and always admitted to being a sensationalist filmmaker.

'A sombra do pai' shot in Butantã

Why do you think Mojica’s films were such a hit?

I believe that every cinemagoer in the world wants to watch an original narrative that brings something different to their life experience, to their cultural repertoire, right? I think that there are many consumers of international horror films out there, people like me who are interested in horror as a beloved genre, who watch and are always seeking out horror movies released around the world. They want a deeper understanding, and always explore or collect the totality of this language, not only what is done in American cinema, in British cinema, but also in Japanese, Italian, Brazilian, Singaporean and Korean horror films. I think there is a bit of a cultural element in this question. What story does the Brazilian horror film tell that’s different from what I’m used to? What kind of people will I see in a Brazilian movie? What kind of scenery am I going to see in a Brazilian film?

I think it’s this curiosity that draws these people towards our films. Festivals like the Fantasia Film Festival in Canada, the Sitges festival, the Fright Fest in London… these bring films from all over the world to create a global panorama of what is made in the genre.

How did you come up with the idea for your film The Nightshifter?

This film is based on a short horror story written by Marco de Castro, and is my second adaptation of it. Marco de Castro, in addition to being a horror writer, was for many years a police journalist and covered many violent incidents in the outskirts of São Paulo as a reporter. So, his horror stories are usually set in the outskirts of São Paulo, and his material is based on his own experience as a reporter. People he met, slums he passed through, massacres he witnessed, he went there and followed the investigation with the police. I think this universe is very rich because it’s very extreme and very raw, and it tells the stories of life in a very harsh reality in the city of São Paulo, on the outskirts of the city of São Paulo.

People say “wow, your movies have a lot of social commentary”. I agree with this statement, but my primary intention was for it to be a horror movie. I thought that the originality of these horror stories comes from the fact that they are set in Brazil and São Paulo and are very Brazilian.

Why do you think foreign directors might be interested in filming in São Paulo or in Brazil?

In addition to the kinds of places you could film in Brazil, the natural beauty of Brazil, aside from that, there’s the fact that I’m Brazilian and I live, I work in downtown São Paulo. That’s my reality. Any horror movie I make here will mean much more to me, so for that reason I am passionate about making Brazilian films.

Brazil has things that other countries have, of course. It has the city outskirts, the slums. But Brazil also has landscapes that you cannot find anywhere else in the world. For example, the Pantanal. I think it’s a very photogenic country. I think that forgein directors, the foreign public should be curious about getting to know Brazil, to understand the moments we experience, what the landscape is like, the urban locations, the natural resources, the real outskirts, the music, the culture… our movies bring some of that. My films don’t exactly bring the best but the most dangerous, the most fearsome, the most violent.

'Pinball' shot in São Paulo

Lastly, how easy is it to produce horror films in Brazil these days?

It’s always a challenge, and now it’s an even bigger one. The Brazilian audiovisual market is in the hands of streamers, and it’s good that streamers have shown interest in making various Brazilian productions, catering to a whole range of audiovisual and cinematographic tastes. Brazilian horror series have already been produced. GloboPlay made

Desalma (Unsoul); Netflix made that zombie one,

Reality Z. I know of other Brazilian horror genre series that will go into production soon.

I think that fantastic Brazilian films will emerge even during the drought that the industry is going through now, and I think it will last for a few years thanks to the funding of streamers. I don’t believe it was just this technology that created this new wave, this spring of Brazilian horror cinema, from 2008 until now. I think it has helped many horror short films emerge, but very few feature films have been made from beginning to end. What really sustained our little genre production was the public money from Brazilian federal and state grants, which have now almost completely stopped.

Thank you Dennison for your time. And for sharing your essential viewing list with us (see below). I would also add to your list the film Pinball – a short directed by Ruy Veridiano and shot by DoP Alziro Barbosa. It’s the story of a young man who attempts a voodoo spell that goes wrong, runs from the cemetery and finds himself face to face with Death in a badly-lit run-down arcade. He attempts to trick Death in a final game of pinball.

'Pinball' shot in São Paulo

Dennison Ramalho's top Brazilian films to watch

Central do Brasil (Central Station)

Walter Salles, 1998

Cidade de Deus (City of God)

Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund, 2002

Terra em Transe (Entranced Earth)

Glauber Rocha, 1967

Eu Matei Lúcio Flávio (I killed Lúcio)

Antonio Calmon, 1979

Pixote, a lei do mais fraco (Pixote: the survival of the weakest)

Hector Babenco, 1981

Bacurau (Bacurau)

Kleber Mendonça and Juliano Dornelles, 2019

Mato eles? (Did I Kill Them?)

Sérgio Bianchi, 1982

Cronicamente inviável (Chronically Unfeasible)

Sérgio Bianchi, 2000

Dennison Ramalho's top Brazilian horror films

Mangue Negro (Mud Zombies)

Rodrigo Aragão, 2008

Cemitério das Almas Perdidas (The Cemetery of Lost Souls)

Rodrigo Aragão, 2020

O Animal Cordial (Friendly Beast)

Gabriela Almeida, 2017

Morto não fala (The Nightshifter)

Dennison Ramalho, 2018

A Sombra do Pai (The Father's Shadow)

Gabriela Almeida, 2019

As Boas Maneiras (Good Manners)

Juliana Rojas and Marco Dutra, 2018

Share this story:

Get the latest news straight into your inbox!

Contact Us

Read another story