On Location: The periphery of São Paulo in photos

A photography collective from the low-income outskirts of São Paulo is the focus of our first On Location column, celebrating Brazil's stunning locations and creative cultures.

The city of superlatives is how the guidebooks sometimes refer to São Paulo: South America’s largest city, home to the world’s largest Gay Pride parade, the biggest Japanese community outside Japan… the list goes on. Some sides of the city, however, rarely make the spotlight, and when they do, it’s negative press. The city’s favelas, for example, make the international headlines for drugs, armed police operations, landslides and – most recently – the devastating effects of Covid-19. They’re one of the top locations for the crews that Story Productions fixes or films for, most recently for news crews from

ITN and a handful of other documentary productions we’ve shot over the past year during the pandemic, which are all still under wraps in post-production.

São Paulo is a city of paradoxes, and foreign production companies often have a preconceived idea of what to expect from the city. When it comes to favelas, in particular, the stereotypes become self-fulfilling prophecies when foreign crews come with a fixed idea of the images they’re looking to capture. We’re hoping to counter some of these stereotypes with a monthly column about locations in São Paulo as well as across Brazil that celebrate the creative cultures and stunning locations that the country has to offer.

To kick this new On Location column off, we’re looking close to home, to São Paulo’s suburbs, and in particular at one of the many creative cultures flourishing in the city’s poorest neighborhoods: photography.

This month is the start of the

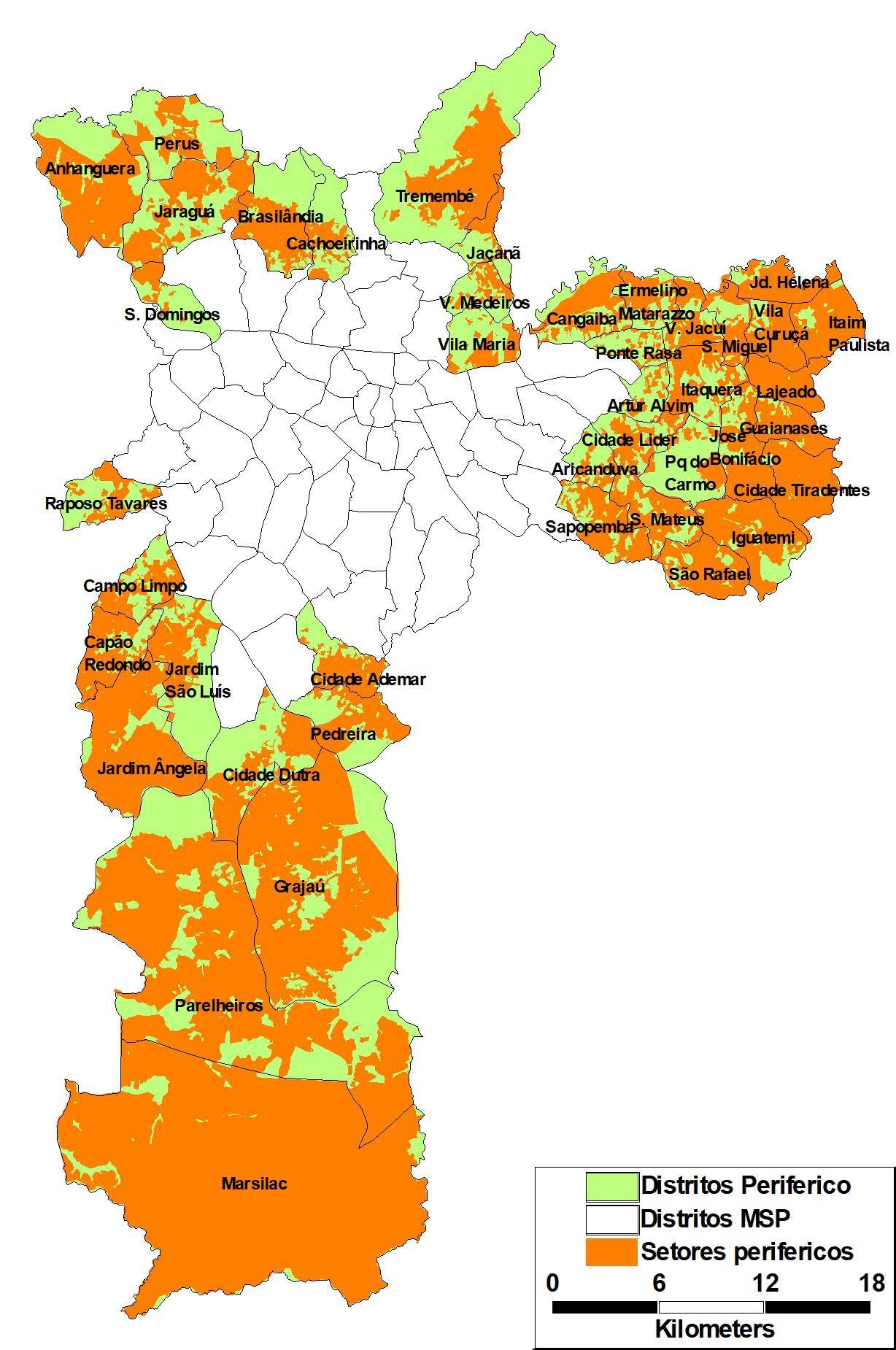

Festival de Imagens Perifericas – “Festival of Images from the Periphery”. It’s the first edition of a photography festival about life in the periferia – a term that denotes the geographical as well as socio-economic margins of São Paulo society.

The academics define it by indicators such as low income, low education, poor healthcare and poor quality housing. For professional photojournalist José Cícero, it’s simply morro (“hill”) versus asfalto (“asphalt”).

“The periphery is everything that surrounds the city,” he explains. “It’s where the favelas are, although there are favelas in the city centre too, but the periphery is basically where the poorest people are, classes C, D and E.”

Breezeblock suburbs

Unlike in North American or some European cities, where the outskirts of a city are often associated with comfortable, middle-class ideals, the suburbs of São Paulo tend to be the poorest, distant from employment and involving hours-long commutes to commercial districts. The reality for most residents of the periphery is one of daily struggle, cramped in small houses made from unplastered, unpainted breezeblocks.

The periphery in São Paulo is home to more than 2 million people. Culture there has always been strong – samba, for example, is one of the oldest expressions of periphery culture. But in the last two decades, talent from emerging creative scenes in the periphery has burst into the mainstream; musicians like Emicida and Criolo, and muralist Eduardo Kobra have become international names. In 2019, one of Netflix’s biggest hits in Brazil was

Sintonia, a series about teenagers in a São Paulo favela, which has been commissioned for a second series. Three months ago, Netflix launched the documentary film

AmarElo, mixing Emicida’s music with a moving history lesson on Black culture in Brazil.

For Cícero, the periphery is his home and the focus of a photography collective that he is a founding member of –

DiCampana. The collective wants to break down negative stereotypes by publishing powerful photos of daily life all over the São Paulo periferia, north, east, south and west. Some of the images are in this month’s Festival of Images from the Periphery, printed as posters and pasted on to walls, bridges and underpasses around the city as lambe-lambes – a very Brazilian, political form of expression.

Born in protest

“This festival opens a window for incredible photographers from the periferia to talk about their work, where they’re from and what they think,” says Cícero. “It shows that photography doesn’t need to be elitist.” Cícero explains that a number of photo collectives emerged in São Paulo in 2013 – SelvaSP and Manana to name just two – in response to a wave of protests that were sweeping across Brazil.

“We saw these collectives photographing the city but we felt that the periphery was missing from this visual language. It wasn’t represented by the people creating this coverage.” In response, DiCampana was founded in 2016, one of the first collectives to focus on representing the periphery. “For a long time in photography, we’ve been praising the same people, really important people for Brazilian photography without a doubt, but there is a lot of new talent emerging, people with different perspectives and different techniques.”

Photography is just one form of creative expression gaining recognition as part of “periphery culture”. Saraus (open gatherings that celebrate varied artistic expressions) have become a regular event in some parts of the periphery (pre-pandemic) since the turn of the millennium, with young and old listening to poetry in bars on the weekend. There are now literary festivals and theatre festivals, too.

“There are so many places in the periphery where we see that the culture is really pulsating,” says Cícero. “In the 90s, we had to go to the city centre to have access to culture. Now we don’t need to leave the periphery. And it’s not just that it’s closer to us. We, the residents of the periphery, are creating it. It reflects our daily life, too. When you go to a gig or listen to poetry in a bar, it’s people talking about racism and about really important social issues. These cultural spaces spark debate, and they connect these issues to the visual medium.”

Questions of colour and Covid

Questions of race and racism are still at the forefront in a city where people of colour represent the majority of the population from the periferia and yet remain a minority across certain sectors, including the media, for example, as is highlighted by research from Énois – a journalism school for youngsters from the periferia.

By way of comparison, people of colour comprise 60.1 per cent of the population of Jardim Angela, in the south-west periphery of the city, whereas people of colour are just 5.8 per cent of the population in the wealthier, more central district of Moema, according to data from the Map of Inequality, which is published by

Rede Nossa São Paulo network. “The higher the percentage of people of colour, the lower the average family income of the neighborhood” is how an article in

Brazilian newspaper O Globo puts it.

The periphery of São Paulo is comprised of 42 districts – 1,086 km2 of the city’s total of 1,528 km2. The total population of these districts is 7 million people of which 2 million live in what is termed periferia, according to socioeconomic indicators such as low income, low education, poor healthcare and poor quality housing.

The pandemic has hit communities in the periphery especially hard over the last year, and young creatives are sharing their take on it not just through photographs, but also video. The DiCampana collective recently produced this documentary about homeless people in São Paulo during the pandemic, for which they spent 2 months filming in an occupation.

Zalika Produções is an independent production company from the periphery focusing on Black visibility. Their most recent production, in 2020, was this documentary called

System Pandemic: the portrait of inequality in Brazil’s richest capital.

Audiovisual collectives are also emerging in the periphery. Coletivo Nossa Tela, Coletivo Mundo em Foco, Gleba do Pêssego and Coletivo Favela Atitude have produced a mix of documentary and fiction set in the periphery. Alternative streaming services are launching, such as Coletivo Transformar and "daQbrada" – an open, online community where users can upload their own short films and documentaries, giving visibility to independent productions from the periphery.

The three current members of the DiCampana photography collective are, from left to right, Léu Britto, José Cícero and Gsé Silva

If you would like to collaborate with young audiovisual professionals from São Paulo, or arrange a shoot in the periphery, please get in touch.

Related articles

Share this story:

Get the latest news straight into your inbox!

Contact Us

Read another story